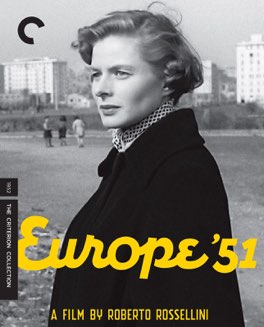

ROBERTO ROSSELLINI

Europe ’51

This is a film about the things we do to people who exist outside of our notions of what’s reasonable or normal behavior. In this case specifically, it’s the Good Samaritan, who wants to help others to a degree that we deem unhealthy. Supposedly, director Roberto Rossellini conceived of this film while shooting his previous film, The Flowers of St. Francis, a biopic about the Italian Catholic monk of the same name. During the filming he wondered what would happen if someone like St. Francis were to exist in the post-war world he lived in, and a few years later he made a film examining that idea.

The story here follows a wealthy socialite named Irene, played by Ingrid Bergman at her least objectionable, who is racked with guilt over the death of her young son. She blames and hates herself for his death and is completely at a loss of what to do. Her husband’s cousin, who is an avowed Communist, attempts to help her by showing her that she can do something for the poor people of Rome. She immediately latches on to this idea, but after working in a factory for a day to help a new friend she’s made, decides that Communism is too anti-spiritual for her, that she wants to bring the love of God to the people she meets. This eventually leads to her having run-ins with her family, the police, and the medical community, and that’s what the rest of the film focuses on.

As I said, this film was made to examine what would happen if a female Catholic saint were living in post-war Rome in 1951. And the answer, at least according to the Neorealist Rossellini, isn’t good. The various people in her life distrust her motivations to the extreme. Her husband, for example, is convinced she’s cheating on him, and cannot begin to understand that she just wants something different and more fulfilling from her life. Even the people she’s helping aren’t particularly nice to her. At one point in the film she’s helped a prostitute that she met back to her house, one who is dying of tuberculosis, and the woman barks orders at her with no sense of thankfulness at all. But even with the lack of compassion or empathy from many of the people around her, she continues to give everything she has to literally anyone who crosses her path.

It’s an interesting idea for a film, and it did lead me to think about how I would perceive someone like this. We see Irene’s full set of motivations and actions, and even then she does come off as unreasonably interested in helping others. It’s a sad commentary on our society that the idea of someone who simply wants to help anyone, even those they don’t know, and even those who aren’t “good” in the classic sense, scares and confuses us. I think that in order for someone to be able to successfully live the kind of life that Irene is attempting, they would have to be blessed by an organization that we already understand. What I mean by that is that if Irene were a nun, or a social worker, we would totally get what she was doing and why. But because she’s simply a formerly spoiled socialite with a lot of money, we are completely suspicious of her motivations and actions. Rossellini portrayed exactly that, over fifty years ago, and if anything I think it would be worse today.

The film definitely has me thinking about the way we treat the people around us. Most of us pay some lip service to the notion that we feel bad for those less fortunate than ourselves, and many of us attempt, in some small way, to help do something about it. But very few of us ever really experience the people we want to help, on their own terms. Perhaps the most notable thing about Irene’s character in this film, is that at no point is she judging any of the people around her. Even when it would seem almost impossible for most people not to. Irene is a woman who has spent most of her life in relative comfort, but she shows no sign of any distance from the people she meets in this film. I don’t think it’s healthy to give yourself completely to those around you, but I do admire and strive to achieve a better ability to fully engage with the people I meet. Irene has lost any concern for her own well being and that’s not a good thing either, but this film definitely has me thinking about the reasonable middle ground.

The ideas that make up this film are very interesting, but sadly the film itself I found less so. This time it wasn’t even about my general dislike for the acting of Ingrid Bergman, as chronicled in several of my previous essays here, most recently in the previous Rossellini collaboration I watched, Stromboli. Bergman was surprisingly competent in the very difficult role of a woman who goes from being a spoiled socialite to, essentially, a saint. The problem was really that the film around her was somewhat overly burdened with a need to contrast what was happening to her character with a bunch of melodrama. The various interactions between Irene and her husband, for example, grew extremely tiresome as the film went on. Also, the acting of basically everyone else in the film was fairly terrible, which didn’t help at all.

The other problem I had with the film was that the presentation of the saintliness of Irene’s character, and the response it drew from those around her, were so over the top that it ventured into absurdity. The political statements about the nature of work and life in post-war Italy are admirable, but they are so heavy-handed and obvious that it actually detracts from the subtler point Rossellini is attempting to make about our relationships with others. Still, I much prefer a film that’s attempting to say something and fails than one that says nothing at all. This film is definitely trying to achieve something, and while it ultimately falls a bit short of its goal, I enjoyed watching the attempt.