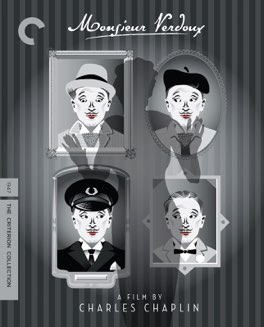

CHARLES CHAPLIN

Monsieur Verdoux

A lot happened in the world between the release of Charlie Chaplin’s previous film, The Great Dictator, in 1940, and the release of this film in 1947. The United States entered and exited WWII, allied with and un-allied with the Soviet Union, and went from being an isolationist nation to being a world superpower. Perhaps most crucially for this film, the true horrors of WWII were revealed, causing Chaplin to view his previous film in a very different light than he had when he made it. All of that history feels completely embedded in this film.

This is the story of the eponymous Henri Verdoux, a character based on real-life serial killing Bluebeard, Henri Landru. The film’s Verdoux is a former bank examiner, who has lost his job in the Great Depression. To make ends meet for his family, he takes to marrying rich widows and murdering them for their money. The film alternates between his juggling of the various women he’s married to, his relationship with his original wife and child, and his attempts to avoid prosecution for his crimes. It’s a darkly comic tale, and one that spends a lot of its time attempting to make the audience sympathize with its murderous central character.

It’s this sympathy that provides the interest for me. The central idea of this film is that the evil nature of the world, and the cruelty exposed through WWII and its aftermath, essentially makes everyone complicit in Verdoux’s crimes. Verdoux is in this sense no different from the world, certainly no better, but also no worse. It’s all just business. Verdoux is a lowercase c criminal, but the world is an uppercase Criminal place, where someone like him simply falls naturally out. He’s simply a mirror held up to society; he represents the logical extreme of the current state of affairs.

It’s a dramatic turn from the pleading for tolerance in The Great Dictator. There is a moment near the end where Verdoux makes a similar appeal to the audience, but with an entirely different message. This time, he equates the killing he has done with the nature of the world around him, claiming to be simply a byproduct of its insane desire for mass death and destruction. It feels like Chaplin reacting to what he has seen. It’s heartbreaking. This is a cynical film, with very little hope left. I totally understand why audiences of the time felt completely unprepared for this film, and I’ve certainly seen better black comedies, but for me the ideas presented made it more than worth seeing.