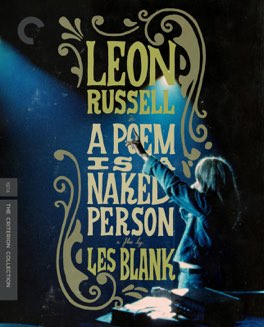

LES BLANK

A Poem is a Naked Person

The first time I saw this, it was at a local theater, with Harrod Blank in attendance. Harrod is the son of the film’s late director Les Blank, and the Q&A that followed was the first time I learned about its tortured history. I was there because I loved the short films Criterion included in their Les Blank: Always for Pleasure release, which was my first exposure to Blank’s work. I was not there for a documentary about Leon Russell. In fact, I had no idea who Leon Russell even was, or that he was the subject of this film. What I got was also not really a documentary about Leon Russell, which has a lot to do with why this film was only finally released in 2015, forty-one years after it was initially completed.

The story of how this film came to be is that musician Leon Russell, and his producer/business partner Denny Cordell, had seen Blank’s previous film about Lightnin’ Hopkins and decided to hire him to do a film about Russell. I’m honestly not sure why they thought that was a good idea. Blank’s films are incredibly personal, focusing less on their subjects, and more on the world according to Les Blank. I can’t really understand how they could have watched The Blues Accordin’ to Lightnin’ Hopkins and thought the man who made it would do a good job as a work-for-hire filmmaker. Then again, even after absorbing all the extra materials Criterion included with this release, I still don’t really have any idea what Russell was trying to achieve with this film anyway.

What I do understand, are his reasons for not allowing the film to be released when it was completed in 1974. Russell has said he felt the film was more about Blank than about himself, which is a claim I would definitely agree with. I can absolutely understand how Russell could feel, when he saw the assembled footage, that he had been duped into creating a film about the world Les Blank found around Russell’s home in Oklahoma, rather than any kind of film about Russell himself. A lot of the footage in this film has only a minimal connection to Russell, and some of it has absolutely no connection at all. Even the stuff that does have Russell in it doesn’t really explain who he is, or always show him in the most positive light. I find it endearing, but I can see how it might have been upsetting for Russell, and how he might have thought he didn’t exactly get what he paid for.

Of course, as I said, I had no idea who Leon Russell even was when I first saw this film, which might be why I don’t really care that it doesn’t do much of a job of telling me. That this is another trip into the wonderful world of Les Blank, rather than a documentary about a musician I don’t particularly care about, is actually a strong positive for me. Instead of focusing on the man, we get another taste of the idiosyncratic way Blank saw the world around him. The film is full of the goofy details he was so adept at capturing, and the fascinating way he edited them together, to create something that functions as a kind of narrative, but more in the feel sense than in the tell sense. As with the previous films of his I’ve seen, it was a delight to be able to view the world through his inimitable eyes.

It does raise a question though, as to what the relationship should be between the patron and his work-for-hire filmmaker. Should Russell have gotten what he intended, when he hired Blank? I suppose so, technically, but I think if you hire a true artist, you really shouldn’t want to dominate their work with your ideas. Otherwise, what’s the point in hiring them? There were undoubtably any number of dependably talented technicians Russell could have hired, who would have made the film he wanted in a competent and professional manner. Whatever film that would have been, however, would probably be of little memory or renown today. We’re lucky that instead of going that route, Leon Russell rolled the dice with an artist, and while he initially felt he lost that bet, he finally realized what he had on his hands, and allowed it to be shared with the rest of us.