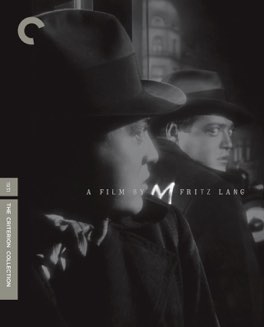

FRITZ LANG

M

I’m trying something different this time around; I’m writing about this film for the TCM Discoveries Blogathon hosted by The Nitrate Diva. This is the first blogathon that I’ve participated in, and I’m very excited to be a part of it. This one in particular, is to celebrate TCM’s new tagline “Let’s Movie,” their associated event, the Let’s Movie holiday. The challenge for the blogathon is to write about a film you first saw via the always excellent TCM, and I chose this one. Now then, with that taken care of, on to the film!

I am a lover of the films of Fritz Lang. Long time readers may remember my glowing praise of Ministry of Fear, and this film only added to the extreme heights in which I hold the man’s work. What fascinated me this time though, was less the technical skill achieved in the filmmaking, although it was certainly present, even in this much older work. No, what compelled me this time was the ideas being presented, and the audacity of Lang to present them at all. A film from 1931 that depicts, with subtle nuance, the crimes of a pedophile, and child murderer?

The film opens with a group of children performing what is definitely the creepiest version of eeny, meeny, miny, moe I’ve yet encountered. A young girl is picking which of the assembled children will be the next victim of a child murder who has been terrorizing Berlin. From there we follow along as the next murder happens, that of young Elsie Beckmann. The film immediately lets the audience in on who the killer is, and the rest of the story follows what happens as the police, and eventually the local crime syndicate, attempt to capture him. The police are seen raiding houses and clubs, and generally misusing their power in the name of order. The criminals react naturally to this disruption of their business by deciding to find the man responsible and deal with him themselves. What happens next is better left to the first time viewer to discover.

It’s an absolutely astonishing film, and one that clearly shows that Lang was already at the height of his craft. This was his first talkie, and yet he already has an incredible understanding of the power that the new technology could add to his story. There are wonderfully used moments of pure silence in the film, as well as the use of sound to convince the audience of things that would previously have needed to be filmed and shown directly. The choice to make the killer whistle Edvard Grieg’s In the Hall of the Mountain King, incidentally a favorite of mine, is absolutely perfect. It creates a palpable sense of dread and horror, with pure atmosphere, rather than explicit action.

What struck me about the film though, was the way it presents the culpability of the man who has admittedly committed these horrific acts. Child molestation and abuse are crimes that are universally reviled by society. Even murderers are not held in the same low opinion as those who prey on children. This film presents the idea that the killer, Hans Beckert, might be compelled to perform his monstrous acts, and that he therefore might not be held responsible in a conventional sense. The film is remarkably open-ended here, refusing to pass judgment on either side of the debate. Should people whose crimes are compulsions be punished in a reasonable society? Should they be regarded as criminals, or are they victims of a medical condition that should be treated?

The film also does a fascinating job of portraying the kind of mass psychosis that comes from fear, and the effects it has on various power structures. The general populace is shown descending into a paranoid aggressive mob, their fear stoked by suspicion, or the most circumstantial evidence. The ruling powers use this fear, as well as a desire to solve the horrible crime, to enact what are extremely liberty denying measures. The city is essentially under martial law, and the population living under constant police watch. That the film was made only a few years before Germany was occupied by the Nazi’s, makes it that much more of a powerful statement.

These are complex arguments in any era, but all the more astonishing coming when they did. This film was released in Germany in 1931, only a year after Hollywood adopted the self-censorship of the Hays code, and three years before all of the major studios finished fully implementing their support of it. The film makes a powerful case against the unconditional support of authority, something the Hays code strictly forbid. The Nazi’s similarly, and unsurprisingly, looked unfavorably on this aspect of the film. It’s an incredibly scary thing to think about; the idea that these two groups agreed on this point, and it should give us all something to ponder. In that light, this becomes an even more astonishing relic to me. It’s final argument, that justice doesn’t bring back the dead, and that parents should watch more closely over their children, is yet another chilling bit of realism to consider.