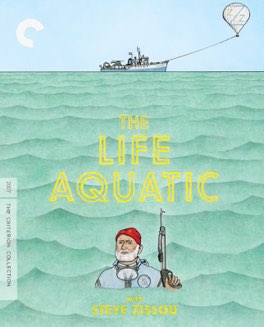

The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou

This has always been a remarkable film to me. It’s definitely Wes Anderson’s most controversial film, the only one where the critics really scorched him.

I never understood the hate people have for it though, for me it’s an amazingly powerful film that has the ability make me both happy and sad at the same time, sometimes in the very same moment. All of Anderson’s films are, ultimately, about fatherhood, and this is no exception, but it’s perhaps the saddest take he’s done on the topic.

It’s about the need to grow up, to recognize that in having a child you can no longer be a child yourself. It’s about a man having to face both his own mortality and his own failures at the same time. And, it’s all wrapped up in the most whimsical take on magical realism that Anderson has maybe ever done. It’s a masterpiece.

The story is lightly based on the exploits of real-life ocean adventurer Jacques Cousteau. Here he is personified by Bill Murray, in perhaps his most powerful role, that of the eponymous Steve Zissou. At the beginning of the film he’s just completed his latest documentary, during which his best friend has been eaten by what he refers to as a “Jaguar Shark.” No one knows what will happen if Zissou actually manages to find this shark, or if it even really exists at all, but he’s determined to search for it in revenge for the death of his friend.

At the party before they launch, Zissou is confronted by a man claiming to be his long-lost son, played by Owen Wilson, and with none of his usual self-referential pastiche. Zissou immediately asks him to join the crew and they head out on a series of adventures, most of them disastrous.

Along for the journey is also a pregnant reporter, played perfectly by Cate Blanchett, who inadvertently causes a rift between the new father and son. And, as a special treat, making an appearance here as a bond stooge, is Bud Cort of Harold and Maude fame.

Zissou represents a man who has never grown up, not even a little. There’s a very telling quote in the middle of the film, when Wilson’s Ned Plimpton asks Zissou why he has never contacted him, given that he always knew he probably had a son. Zissou says “Because I hate fathers, and I never wanted to be one.” Zissou never wanted any actual responsibility, and he didn’t think he could handle it if he got it.

Instead he’s like an eternal eleven year old, running around having crazy adventures and doing the kind of things that young boys dream of. He’s like a real-life Peter Pan, and the presence of an even possibly-his-son is enough to send him deep into what-does-it-all-mean territory. It combines with his already extreme sense of weariness and ennui, partially caused by the recent death of his best friend, but also because he’s starting to get older, his films are no longer in demand, and he’s being forced to try to figure out what it all means.

This isn’t something he’s emotionally equipped to deal with, so he spends most of the film lashing out at the world around him rather than looking inwards for understanding. When he finally does start to examine himself it’s fascinating what he finds.

I think the reason I connect so strongly with this film is that my own father is a bit of a Steve Zissou type. Certainly he’s nowhere near the level of comic absurdity that the film version is, but there are still more than a few similarities. I have a “cool” father, one who had more amazing adventures before I was born that I may ever have.

He climbed mountains no one had previously climbed, was a pinball champion, pioneered medicine for various diseases, and all other kinds of incredible things. It’s perhaps what makes me a bit of a braggart, not to use him as an excuse, but I think I’ve always been trying to live up to the insane level of achievement he represents.

All sons want to impress their fathers I think, and I’m a super stereotypical example of this. At the same time, my father also has had a bit of trouble “growing up” at times, although he certainly handled it better than Steve Zissou does. Maybe I could say that we represent the realistic version of this absolutely absurd story.

Anyway, it means that this film resonates with me in a way that’s probably quite a bit different than it does for the average viewer. Even without that touchstone, though, this is a truly amazing film that deserves a second look by anyone who thinks it doesn’t stand up well to the rest of Anderson’s output.