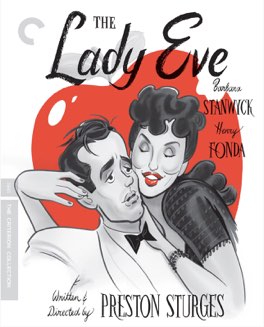

PRESTON STURGES

The Lady Eve

The brilliance of screwball comedies is the way they set things up so that absolutely banana scenarios seem somehow plausible within the context of the story. Sure, the audience is still saying “what?!?” all the time, but more in awe rather than in rejection of the possibility. They require, and provide, the utmost in suspension of disbelief and I am absolutely here for it.

This tells the ludicrous story of Charles, a young, supposedly naive, scientist son of a fabulously wealthy ale family. He’s returning home from a year in the Amazon when he meets Jean, a con-artist. Her plan is to make Charles love her, propose marriage, and then she’ll milk him for all he’s worth. It mostly works to a tee, but, of course, she falls in love with along the way.

She falls in love and decides to go straight, but just before she can have her happily ever after, Charles is alerted to her criminal past and leaves her. She’s left infuriated, both that he couldn’t overlook her past and embrace her honest love, and also, paradoxically, that she didn’t get away with her crime. Her solution to her hurt feelings is to head to his house, put on a fake English accent, change nothing else about her appearance, and pretend to be a totally different person named Eve and attempt the whole thing all over again. As you do. It’s absolutely brilliantly ridiculous.

I said earlier that Charles is supposedly naive. I say supposedly because, while his innocence is definitely a defining feature of his character early in the film, there are some signs that he’s not as on the up-and-up as he claims. While romancing both Jean and Eve he uses an identical line to try and woo them. It’s a small thing perhaps, but the film dwells on it, and it really underscores that he’s probably a lot more aware of what he’s doing than he lets on. He’s ultimately something of a creep, and a snobbish one at that.

It makes a huge difference. His inability to treat Jean/Eve with kindness, when we know she’s gone legit, helps us to keep rooting for her, even though she’s a literal con-artist. Because her mark isn’t as innocent and clueless as he would want us to believe it levels the playing field. It makes him much more of a player in the game, which means that he’s suddenly much more of a fair target for her various machinations.

In addition, his response to both Jean’s criminal past, and to the details of a previous love life that Eve shares, make him a far less sympathetic character. That also provides one of the primary elements of successful screwball, which is that all of these tricks and antics are justified because these are clearly two complicated and far-from-perfect people who deserve each other. It’s a small thing, but it goes a long way to sell the story to the audience.