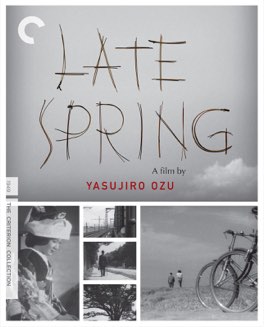

YASUJIRO OZU

Late Spring

Some directors take me a while to warm up to. Maybe I don’t like the first film of theirs I watch, maybe I don’t like the first few. Perhaps their films initially seem uninteresting, or maybe I just can’t connect to what they’re trying to say. Sometimes I never change that opinion. Every once in a while I watch a film from a director I’ve never experienced before and I just fall completely in love.

That happened to me with the previous film I saw from Yasujirō Ozu, An Autumn Afternoon. I was completely stunned by it. Certainly there were issues, and I talked about them on my old movie podcast with my wonderful friend Christa Mrgan, but I was still enraptured. As it turns out, that film was the last in a particular period of Ozu’s filmography, and in fact was the last film he made overall. This was the first of that period, and I loved it maybe even more.

The story is superficially fairly similar. Both films feature a widowed father who has decided he should find a husband for his marriage age daughter. In both cases the conflict is that he realizes he’s being selfish by keeping his daughter at home rather than allowing her to move on to the next phase of her life. Where they differ, is primarily that this film does a lot more to examine the consequences of those choices.

Noriko, played by one of my all-time favorite actors Setsuko Hara, doesn’t want her life to change. She doesn’t believe in the inevitability of marriage. She likes living with her father and taking care of him. She’s torn between a modern view of the world, one where she should be able to make her own choices and might choose to remain alone, and a traditional view where she is subservient to her father and should allow him to find her a husband. It’s a fascinating look at the process Japan was undergoing post-war of cultural upheaval.

Ultimately the film doesn’t really settle on one side or the other of this debate, and I think that’s wonderful. Because it’s not a debate that can be conclusively answered. It’s a tension that exists today, as we each have to decide how beholden we feel to our elders, to our past, to our culture, to ourselves, and to the other people in our lives. If the film had a pat answer, or an unambiguously happy ending, it would undercut that point. This stuff is messy, and that’s ok. It’s literally life.