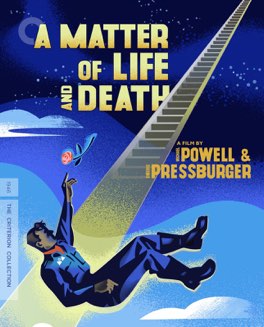

MICHAEL POWELL, EMERIC PRESSBURGER

A Matter of Life and Death

The idea that love is the only point to life is certainly not a new one for the film industry, nor for storytellers in general. It’s been the primary subject of stories in the English language going back long before Shakespeare, and features prominently in French literature even before that. I don’t know much about comparative world literature, but it wouldn’t surprise me at all to learn that those are not the only places one can find it. What makes this film so interesting is that it tries to show the details of what that actually means.

This is the story of an RAF pilot named Peter, who is shot down during World War II. His plane is damaged, his crew has bailed out, and only he is left. He has no parachute, as it was destroyed in the attack that rendered the plane inoperable. He is preparing to jump, to his certain death, when he calls the nearby radio tower to let them know what he’s doing. During that brief call he manages to fall madly in love with the young American woman volunteer who answers, and then he jumps.

When he wakes up he assumes he has arrived in the afterlife, but in fact he has somehow survived. The bureaucracy in Heaven is unhappy, as he was supposed to die, and they want him back. But now that he’s made it, and found the woman from his radio call, he doesn’t want to go. The film follows the legal case he makes to the powers that be in Heaven that he should be allowed to live. Simultaneously we see Peter’s courtship with June, the woman he met, and his encounters with a doctor friend of hers who tries to solve his problem medically.

What’s so fascinating to me is the way Heaven is portrayed. The film is in technicolor, but Heaven is in black and white. Our world is messy and real, whereas Heaven is staid and ultra modern, almost brutalist in its design.

I don’t think the message here is the same as in, say, Jacques Tati’s work, because the modern world hadn’t really arrived yet, but it has almost the same affect. In Heaven things are highly organized, with new arrivals getting their wings wrapped in some kind of plastic. Things are ordered, forms are filled out, everything is in its proper place. It’s not particularly unpleasant or anything, it’s just a bit cold. The real world is far messier, and interesting, and the film is clearly on the side of remaining in the real world as long as possible.

It’s an almost shocking perspective for the era it was made in, but it remains remarkable even now.