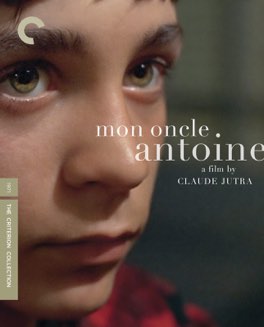

CLAUDE JUTRA

Mon Oncle Antoine

I’m writing for another blogathon and I couldn’t be more excited. This one, hosted by Speakeasy and Silver Screenings, is focused on films from Canada. The challenge was to write about a film, or an actor, or a movement, that came directly from that wonderful country. For my entry, I chose to write about this Claude Jutra film from 1970s Quebec. From 1984 to 2014 it was officially recognized as the greatest Canadian film of all time, according to the Toronto International Film Festival’s once a decade poll.

With all that housekeeping out of the way, what is this film all about? It tells the story of a 15-year-old boy named Benoît, as he comes of age in a small mining town in 1940s Quebec. He works at the town general store, owned by his aunt and uncle, the titular Antoine. The film follows a few days in his life, as he gets ready for the Christmas season by decorating the shop, flirts with the equally young girl who works at the shop, and helps his uncle with his side business as the undertaker for their region. Throughout the course of film he comes to understand the frailty of character present in many of his elders, and also begins to explore his own burgeoning personality.

The film also takes place at a fascinating point in the history of Quebec. The late 40s were the time of the premiership of Maurice Duplessis, and his ultra-conservative Catholic party Union Nationale. This was a period in which the majority French speaking population had no ability to get better than menial jobs, working for English speaking bosses. It was a time of religious-based social policy, and essentially no social services. The film takes place in a mining town, right on the eve of a real event, the Asbestos strike of 1949, that led to the Quiet Revolution and totally transformed the province. The evidence of this history is everywhere in this film, but it’s very subtly presented, the focus is definitely on the human drama happening around it.

There’s something so fundamental about the moment you realize that there are no real adults in the world. As young children we imagine that our elders know everything. Or at least that on some level they have their shit together in a way that makes sense. If we contemplate this at all, we might imagine that at some point along the way, we’ll magically figure everything out as well. More likely, we don’t contemplate it at all, and just accept it as an unacknowledged truth. It’s a shock then, when we first begin to realize what a fallacy this notion is. When we start to see that the adults around us are just muddling through as best they can it’s a pretty heavy shock to the system. After all, if they don’t have it together, what does that say about our chances?

At the same time, as the years go by, we realize that we haven’t magically figured everything out, and we begin to understand better the struggles that our parents were going through when we were young. At least that’s what’s happened to me. This process has made me infinitely more sympathetic to my parents part in events from my childhood that I once felt righteously injured by. I know now, as a person closer in age to where they were then, that they were just doing their best. They didn’t have a manual for any of the situations they found themselves in, all they had were their best intentions, and that had to guide their actions. I realize now how difficult I made it for them to do that, and appreciate so much more all that they went through.

Benoît spends most of this film in the middle period between these two realizations. He’s understanding now that his family has no idea what they’re doing, but he hasn’t yet figured out that he won’t either. And so this represents the highest moment of his disappointment in their flaws, and the peak of his own self-righteousness. He sees them as failures to avoid, rather than as the human beings they are, just doing their best to muddle by. The film ends at this point, but if it continued it would likely be followed by some very rocky years. He would be lashing out, full of anger at their frailty, before hopefully finding compassion for their humanity. It’s a beautiful portrait of this singular moment in all of our lives, and it was an absolute pleasure to watch.