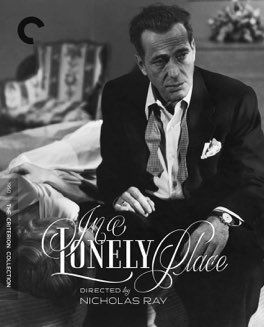

NICHOLAS RAY

In a Lonely Place

I wasn’t prepared for this film. I knew very little going in, other than that it was a film noir, and that it featured Humphrey Bogart in a darker role. I also knew that at least one friend of mine didn’t think the film ended up being dark enough. As a result, I was entirely unprepared for what is a very brutal depiction of the nature of abuse. Bogart’s character is an almost textbook example of an abusive person, full of all the contradictions that encompasses. In that way, I think this is an extremely bold film, especially given the time period it was released. On the other hand, I agree with my friend that the film ends up taking the easy way out, opting to avoid the brutality inherent in the likeliest outcome of its story.

The film follows a witty and violent, mostly washed-up, screenwriter named Dixon Steele. As the film begins, he’s been offered the chance to adapt a trashy romance novel. Not wanting to burden himself with actually reading the book, he invites a young hat-check woman, who has just finished reading it, to come to his house and tell him the story. The next morning he’s hauled into a local police station, and informed that she was murdered, sometime after leaving his house. The police suspect him as the likely killer, even though he has an alibi, provided by a beautiful former actress, Laurel Gray, who lives across from him and claims to have seen the hat-check woman leave his house. Steele and Gray immediately begin dating, and the rest of the film follows the abusive nature of their relationship.

Steele’s character is charming, witty, and talented. He is also jealous, vindictive, aggressive, and violent. The story sets up his love affair with Gray perfectly, as she falls head over heels for him, and then slowly chips away at it. The ensuing destruction is difficult to watch. Early on Gray begins to get some idea of the man she’s attached herself to, but the enablers around him keep talking her out of her suspicions. There is a very real portrayal of the horrible acceptance those who have to deal with Steele have towards his behavior. This is most present in his relationship with his agent, a man he is almost as abusive towards as he is with Gray. The man puts up with it all, because Steele represents his livelihood, in an industry that will overlook almost anything for talent and success.

The film is unflinching in its depiction of the horror of Steele’s abuse. It shows the effects on Gray, as well as others around Steele, and even shows how the fear of further violence compels Gray to classic examples of victim bartering and self-preservation. What I found especially surprising, given the time period of its release, was the length to which the film doesn’t attempt to idolize Steele or his behavior. Humphrey Bogart was a seriously famous leading man in 1950, and especially known for playing cool characters that inspired men to want to be just like him. That he was willing to subvert that persona, to show this real life monster of a person, without attempting to justify or glamorize it, makes the films message that much more powerful.

Where the film falters a bit for me is in the ending. In the original screenplay, the film ends with Steele being arrested. Not for the murder of the hat-check woman, for which he was truly innocent, but instead for the murder of Gray. As she decides she’s had enough, he discovers that she’s leaving him, and kills her instead of letting her go. This is, sadly, the reality of many real-life versions of this story. On the set, however, the director Nicholas Ray couldn’t go through with it, having them simply walk away from each other instead, because he claimed he wanted to show that relationships don’t need to end in violence. This new ending, which was apparently largely improvised, still isn’t a happy one certainly, but it removes the power finishing the narrative could have had. It doesn’t break the film, but I think the original would have been a more honest, if less pleasant, way to end things.