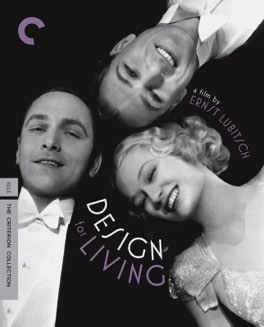

ERNST LUBITSCH

Design for Living

I’m writing for a Blogathon again, this time for what I anticipate will be my last of the year. I really enjoy participating in these events, but I’m working on a variety of new projects and I don’t think I’m prepared for the scheduling commitment an organized event imposes. Still, I couldn’t be happier to be writing for this particular gathering, hosted as it is by the incomparable Movies Silently, Citizen Screen, and Silver Screenings. For my part, I chose to finally watch a film I’ve been looking forward to for quite some time, and I’m happy to report that it was absolutely worth the wait.

What I find most interesting about this film, is how shockingly brazen and open it feels to me. Not as a relic from the past, not in the way that something feels ahead of its own time, but as something that feels ahead of my time as well. This film, from 1933, feels more honest about human relationships and their possibilities than most films today. I’m honestly not sure you could even get away with making a film like this today, at least not without upsetting a whole lot of people. It’s an unsettling thought that we’ve perhaps regressed in our openness over the years.

The story follows three young Americans, who meet randomly on a train to Paris. Two of them, Tom and George, are leftist artists, tramping around Europe with virtually nothing to their name. The third, a young woman named Gilda, is also an artist, but of a professional bent, she’s an illustrator for an ad agency. Both men are immediately drawn to Gilda, and she’s drawn to each of them as well. Initially she dates each secretly, but eventually they all reach a “gentleman’s agreement,” where they will all date, but with no sex. The rest of the film follows the ups and downs of their arrangement, as they attempt to navigate through unfamiliar waters.

There are two fundamental things about this story that I find shocking. The first is that the film passes virtually no judgement on the polyamorous nature of this arrangement. The only character in the film who protests the situation is Gilda’s boss, Max, and he is used purely to deflate the argument. He’s an obsequious company man, a non-artist, who disapproves of the relationship from the start, but is without a doubt the closest thing the film has to a villain. He’s used purely as a foil, an out-of-date fuddy-duddy, and his views are quite clearly not to be taken seriously.

The second is that the main character, and the one who is at the center of this particular arrangement, is a woman. There is an incredible moment in the film where Gilda is asked to choose between her two paramours, and she decries the choice as fundamentally sexist. Explaining that men can be expected to date many woman at once while remaining respectable, she finds it intolerable that she’s not allowed to do the same. The film overwhelmingly agrees with her, and this early victory for feminist thought still bowls me over today.

This is a film that openly discusses premarital sex, without any couching in cute analogies, or wrapping things up in genteel language. The openness of the conversation feels revolutionary even to my modern ears. There is nothing salacious about the conversation, it’s not intended to provoke or astonish. It’s simply discussed comfortably and openly. This lack of stigma would be hard to pull off today, and I can only think of one film that even attempts it, the hardly mainstream Gregg Araki film Splendor. That Lubitsch was making a statement like this in the 30s absolutely blows my mind.