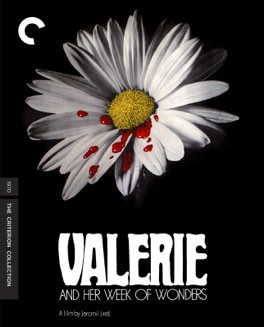

JAROMIL JIREŠ

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders

I was a big fan of the television show Buffy the Vampire Slayer, at one point I even owned the entire run on home video. What I loved about that show wasn’t the acting certainly, which was an extremely mixed affair. It wasn’t the stories necessarily either; they were mostly convoluted, and often absurd in a bad way. No, what I loved about Buffy was that it was attempting to deal with serious subject matter, by appearing to be dealing with almost anything else. It was an entire show done in an allegorical style, and the themes it was actually dealing with were far more real than any casual viewer might imagine. It was an incredibly powerful way to discuss real issues without seeming preachy. This film felt largely the same way, and I enjoyed it for the same reason.

The film tells the story of a thirteen year old girl named Valerie, beginning roughly at the moment she gets her first period. From that point on we enter an almost complete state of dream-logic, representing the inner turmoil that Valerie feels as she processes her entry into womanhood. This turmoil is represented as a series of visually stunning, and seriously confusing, vignettes, mostly centering around a vampiric figure known as the polecat, who may or may not also be Valerie’s long lost father. The polecat arrives to spread chaos and violence around him, and also because he clearly wants something from Valerie. Which doesn’t separate him at all from the rest of the adults around her. Everyone wants something, including her Grandmother, who betrays her to attain a second youth, or the newly arrived missionary priest, who tries to use her body for his own pleasure. Valerie is helped in her quest to simply survive by a man who wants to be her lover, but might also be her brother.

If all that sounds confusing, it’s because it is. The film has the logic of dreams, and, as such, things shift rapidly, and with little warning. One minute a character appears to be dead, the next they’re back and with some agenda. What I found valuable, was to split the film into two layers in my mind. One was simply the incredible and beautiful visuals that I was confronted with, which could simply be enjoyed without worrying too much about what was really going on. The other layer was the ideas those visuals were dramatizing, in the same vein as the Buffy episodes I loved. This is clearly a story about the inner confusion of a young girl who is becoming a woman. She’s aware that her life is changed in some fashion, and that the people in that life clearly want something from her. She’s not quite sure what that something is though, or how she feels about it, or what level of involvement she might want to have.

Valerie appears throughout the film to be constantly shifting her ideas of how she wants to involve herself in the needs of others, while also learning how to protect and defend herself when she doesn’t want to participate. This is dramatized in the dream world as using her magic earrings to save herself when in mortal danger, but also when she gives herself up in various ways to save her vampire perhaps-father. She defiantly martyrs herself in a literal witch burning at one point, due to her refusal to sleep with the super creepy catholic missionary, but she also helps the same man when he returns from the dead.

Throughout all of this, and in maybe the biggest difference from Buffy, Valerie is presented as not a superhero, but rather as simply a perfectly normal young girl. This gives her story even more power I think. Where Buffy could be perceived as extraordinary, and thus an ideal that’s unattainable, Valerie represents any individual thirteen year old girl, and what they might be going through. This lets the film become something that I could see a young person relating too, perhaps far more than we might even want to believe. As a society we are uncomfortable with the idea of youthful sexual awakening, even as we creepily idolize it. This film, in its honest reflection, deals with that idea in a way that I found incredibly refreshing.

It’s also really nice to see the coming-of-age story of a girl, instead of a boy. Really nice, in that it’s a sad rarity in cinema history, but also fraught with some issues. What I mean is that, like Buffy after it, this is a representation of female adolescent awakening, as told mostly by men. The film is based on a novel, written by Czech Surrealist author Vítězslav Nezval. The film itself was directed by Czechoslovak New Wave director Jaromil Jireš. I’m not saying that these men can’t tell a story that exists outside their own personal experiences, but I do think this fact colors some of the details in ways that are a little bit weird to think about.

The one savior is that the film version did have a strong female presence in the form of co-writer and production designer Ester Krumbachová, and I think it’s likely her presence that keeps things from teetering completely off course. The film attempts to walk an extremely narrow path between exploration and exploitation, and to my eye it just manages to stay mostly on the right side of that divide. There are a few questionable moments, but by and large it doesn’t feel like a story meant to fetishize its main character. I am not, however, a woman, nor was I ever a thirteen year old girl. I am, therefore, not necessarily in the best position to judge if the attempt completely succeeds or not. I simply applaud, and enjoy, the effort, because I think it’s an attempt worth making.