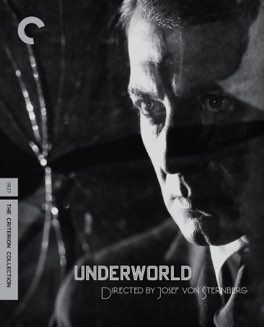

JOSEF VON STERNBERG

Underworld

Josef von Sternberg was searching for something in 1927. He’d been working in the film industry since 1915, in a variety of roles, and had even directed his first feature film back in 1925. He had been hailed as a genius of light and shadow. That first film, The Salvation Hunters, considered to be the first American independent film, was critically acclaimed, but commercially abandoned. He’d been hired by Charlie Chaplin, and then had Chaplin refuse to release his film A Woman of the Sea, and destroy the negatives. He could have decided to just stay in the burgeoning art world that loved him, but he wanted to be a mainstream director. In other words, he needed a hit.

He only got the job to direct this film because Paramount fired the original director Arthur Rosson. They predicted the film would be a failure, and only booked it in one New York theatre. But the word of mouth was tremendous; it was both critically and commercially acclaimed, and won its author Ben Hecht the first ever Academy Award for Writing. The film is a beautiful work of art, in addition to being a rollicking good time. It’s widely credited as the first Gangster film, and certainly popularized the genre for the American public. As that’s a genre that I love, it was incredibly interesting to see this extremely early example. What I found was prototypical in the best possible way, featuring so many of the elements that made later films great.

The film follows the exploits of Bull Weed, a gang leader of criminally unsavory types, who does whatever he wants, whenever he wants. Early in the film a drunk witnesses him commit a crime, and he decides to take the man into his gang, renaming him Rolls Royce and setting him up in style. The film mostly concerns the relationships between Weed, his main lady friend Feathers, Rolls Royce, and Weed’s main adversary Buck Mulligan. Like all great gangster films, there are plans, violence, criminal activity, standoffs with the police, and betrayal. The plot arches in increasingly interesting ways, and resolves in one of the most randomly surprising and pleasant endings I’ve seen for a film of this type. It’s a really fun film.

That ending, which is the type of hollywood niceness that Sternberg had originally avoided in his films, but now felt was necessary in order to secure success, was not popular with the film’s writer Hecht. He had based the story on a real person, “Terrible Tommy” O’Connor, and on his experiences with gangsters in Chicago, and he felt that Sternberg had corrupted the truth behind his tale. Some of the critics of the time agreed with him as well, criticizing the film for being too “Hollywood.” Hecht disliked the changes so much, in fact, that he initially fought to have his name removed from the credits. The studio, working with an unknown director but a very well known writer, understandably refused.

I have to say, I’m really glad that Hecht didn’t succeed in pressuring them to make the film he wanted. The ending we get is so much more interesting, if a little bit saccharine yes, than anything else they could have done. It’s a bit unrealistic for sure, but then this film is hardly a documentary. And, although no one knew this at the time, this film would go on to inspire so many others, so it’s nice that all those other filmmakers have something thoughtful to consider as they plan their films. It has almost certainly led to more interesting work than we otherwise might have had. Not a bad legacy at all.