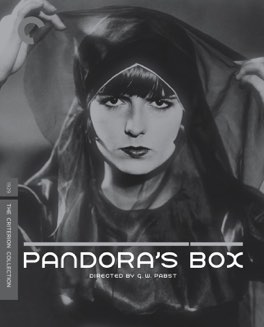

G. W. PABST

Pandora’s Box

I’m once again writing about a film for the benefit of a blogathon. In this case it’s for the Try It, You’ll Like It! Blogathon, which is a theme that resonates strongly with me. It’s being hosted by Sister Celluloid and Movies Silently, two wonderful classic film blogs. For this blogathon I chose to consider a silent film that runs for more than two hours, and presents ideas that are still relevant today, which means it definitely fits into the skeptic-overturning premise of the blogathon.

The silent film era is a fascinating period. I think it’s always interesting, when in the history of an art form, you find a moment so transformational that it bifurcates the before and after almost completely. Certainly silent film resembles post-sound film, many of the later elements are obviously already present. Still, it’s almost completely disconnected, at least in terms of how we must approach it if we want to feel its full potency. It’s a very different form, forcing us to give it almost complete focus or risk losing all track of what’s happening. It’s an essentially visual medium, there is often music, and it does help heighten what’s happening on the screen, but without the visuals we have basically nothing. This particular silent film is notable for having an extremely involved premise, one that was significantly ahead of its time.

The film takes place in Weimar-era Berlin, which was a fascinating period all on its own. It follows Lulu, a young and vivacious mistress to a middle-aged newspaper publisher named Dr. Schön. As the story begins, Schön tells Lulu that they cannot carry on together, as he intends to marry a more respectable woman. Schön also decides to have his son, Alwa, who is Lulu’s best friend, cast her in a musical revue he’s producing. Unfortunately for Schön, he makes the mistake of taking his fiancée Charlotte to opening night, and ends up making out with Lulu in front of her. This leads to Schön deciding he has to marry Lulu, but he’s accidentally shot by her during the wedding reception. The rest of the film is concerned with Lulu’s trial for murder, her escape, and her life as a fugitive from the law.

As I said, it’s extremely involved. What I found fascinating about this film though, was the way that it portrayed its leading lady. Lulu is represented as a shockingly cosmopolitan and sexually vibrant young woman. She radiates sensuality and sexuality as she wanders through the set pieces of her life. Her sexuality isn’t a weapon though, she seems somewhat oblivious to the effect it has on those around her. Certainly she knows how to use her charms to get what she wants, but she does it in an innocent manner. She’s mostly a passive participant in the seduction she supposedly creates, simply by being nice to those around her. It has a devastating affect on almost everyone she encounters though. Certainly she charms all the men she meets, but she also charms another young woman in one of cinema’s first lesbian subplots.

I’ve read many articles about this film that describe Lulu as being responsible for destroying the men she encounters. Certainly their destruction is central to the story. The prosecution lawyer at her murder trail calls her Pandora, for her supposed wantonness. However, I think it’s reductive and missing the point to think about it this way. Lulu doesn’t do anything to destroy these men, they destroy themselves. They don’t see her as a person, the simply see her for her beauty, and her sexuality. She’s not a subject for them, she’s an object, and they destroy themselves “for her” in a way that has no connection to her own will. She’s an innocent participant in basically everything that happens around her; things are simply done in her name by people who think they know what’s best for her.

In this sense, the film is a fascinating deconstruction in the ways that society treats young women. Certainly none of the people who fall for Lulu in this story take ownership for their own choices, they see themselves as simply being under her thrall. Lulu has no agency in this process, however, she’s simply reacting to the choices these people are making around her. She doesn’t even seem to really understand the affect she has, and she shouldn’t have to. These people made their own choices, and neither Lulu, or the film, has much sympathy for what happens to them. Still, Lulu pays for her openness as a victim of the “fallen women” trope. I hope more people can look past their fear of silent cinema and give this a try. You’ll like it!