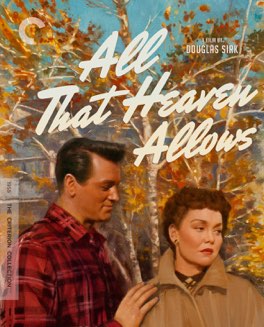

DOUGLAS SIRK

All That Heaven Allows

A good friend of mine died recently, in an entirely unexpected fashion, throwing my life into the usual unpredictability of emotion that an event like that entails. In between the bouts of anger and sadness that I’ve been going through, my girlfriend suggested that we watch a “romantic film”, and this is the one we ended up choosing. It’s my first experience with the genius of framing and color that are the hallmarks of director Douglas Sirk’s work, and it ended up being a wonderful choice for my current mood. This story of love and courage, of stubbornness and conformity, somehow perfectly alleviated my sadness, if only temporarily.

The film follows Cary, a widowed mother of two, whose life has become entirely boring and predictable. Her children are away at college, and she’s tired of the country club friendships available in her upscale suburban town. With an unexpectedly brisk pace, we’re introduced to Ron Kirby, her gardner, and a man ten years her junior. He’s clearly smitten with her, and while it takes some minor convincing, she’s smitten as well. Thus begin a lovely and respectful relationship, one that inevitably triggers all-out chaos in Cary’s life, with everyone from her snooty neighbors to her own children objecting violently to the pairing.

Of the film’s two central notions only one of them really resonates with me as a person living today, instead of the mid-fifties. That’s the idea that we, as a society, are uncomfortable with the notion of our parents, or anyone over a certain age really, acting like people instead of as museum pieces. Cary’s friends and children all want her to become something like a vaguelly-living monument to her dead husband. The notion that she might actually want to just go on living her own life is completely alien to them. Probably the best depiction of this idea is a scene that everyone who writes about this film loves to mention, where her children buy her the ultimate mausoleum, her own television set.

That idea is absolutely still resonant to me as a person living today, and thinking about my own parents and elders. The other notion though, that her friends and family don’t approve of the pairing because of the age difference, that one falls a little flat. I don’t think anyone would care nearly as much today about such a relatively minimal age gap as they did back then. Especially in a post Sex in the City world, I just can’t really accept the idea that it would be anything like this level of scandal. In his homage/remake, Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, director Rainer Werner Fassbinder chose to make the relationship cross-racial instead, and I have a feeling that that will come off as much more realistic to my modern eyes.

A lot has been written of the notion that what this film really represents is a critique of the contemporary upscale American society that it portrays. A word I’ve seen in many of the articles from the film’s reappraisal in the seventies is “scathing.” I did a lot of thinking about this topic after watching the film, and while I do think it’s true that the film is judging society, some of the more grandiose claims are a bit overblown for my taste. For me the message of the film is more about being trapped in societies ideals, and of wanting to find a way to live your life outside of the expectations being placed on you by people who don’t have to experience your day to day reality. Cary’s children, for example, would really like their mother to just quietly exist to serve them, rather than to be her own person in any legitimate way.

I think the film delivers that critique marvelously, in both subtle and extremely blatant ways. What I find less compelling as an argument is that this is an indictment of society on idealogical grounds. To my eyes, this film wasn’t really about using the stuffiness of Cary’s friends to skewer American capitalism or excess, but rather to argue for the perhaps even more radical idea that older woman are people too. In fact, my one criticism of the film would be that it doesn’t go quite far enough in that direction. Cary’s new boyfriend Ron might be something of a Thoreau style beatnik, but he still seems to want to exert quite a bit of dominance over her. The film’s happy ending is certainly comforting and rewarding, but it could have been a much stronger statement if she had decided just to live her life on her own terms, rather than simply switching whose terms she was conforming to.