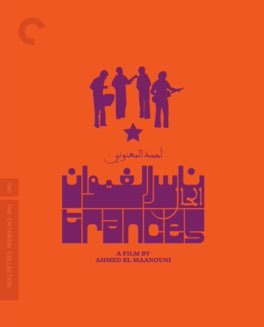

AHMED EL MAÂNOUNI

Trances

This absolutely lived up to its title, which perfectly describes the mood that I was put in by the music I heard. The film, which is a documentary about legendary Moroccan band Nass El Ghiwane, transported me to a completely different headspace. Their music, which is made up of traditional Moroccan instruments, as well as a fretless Banjo, is completely intoxicating. Their lyrics are so different than what you get from Western popular music; this was much more akin to philosophical poetry, and in fact I believe a lot of it is taken from actual poetry.

As I said, this is a documentary about the band Nass El Ghiwane, who officially started in the late 60s but really hit their stride in 1971. The band is one of the biggest of all time in the Arab world, especially in their home country of Morocco. The documentary doesn’t really delve too deeply into the story behind the band; we don’t learn much about where they came from, or how they came together. Instead, the film focuses mostly on a deeper idea of who these people were, presenting them in their natural element and without much in the way of reflection. And, of course, the film features a ton of their music.

The music is centered around one performance in particular, but is also interspersed with various other footage, including some from the earliest days of the band. In between we get many scenes of daily Moroccan life, and the various things the band does when they aren’t on stage. We get shots of them messing with each other, or listening to an itinerant street musician. They clearly love each other deeply and what they’re doing, and it’s great to see them in these more candid moments. It’s especially amazing that the band doesn’t appear to be acting or presenting an image in anyway, I got the sense that this is just who they were as people.

One of the most interesting things about this film was the almost complete lack of celebrity that the members of the band presented. None of them seemed to think they were in anyway stars or separate from their audience. The film shows them going about their daily tasks without any ostentatiousness or financial flamboyance. They come off as just being overjoyed that they get to be artists for a living, but without any of the trappings we would associate with Western musicians in a hugely successful band. They have been called the Moroccan Rolling Stones, but that band is almost defined by their rock star behavior, none of which I found here.

In fact, the band make a point of mentioning that they consider themselves simply artists, and that they would be doing art even if they couldn’t be in this band. At one point they discuss what they would do if they were suddenly not allowed to perform, something that wasn’t exactly out of the question at various points in their history in Morocco. The answer that Laarbi Batma gives is amazing. He says that first he would fight for his right to sing and make music. But that, ultimately, there are many kinds of art and he would simply find another way to express himself. At no point does he suggest that he would try and do anything outside of creative pursuits, marking art is clearly just who he was.

Another thing I found compelling about Nass El Ghiwane was the content of their lyrics. Morocco gained independence from France and Spain in 1956, but almost immediately afterwards the country was thrown into a period of martial law, a period that only ended in the late 90s. That means that most of the history of this band was made in a country that had strict censorship and political oppression. They were apparently somewhat protected from censorship by their King, who was supposedly a fan of their music, but it was still not exactly an environment where it must have felt easy to take any kind of stand on real issues.

That’s what makes it even more amazing that their lyrics refelct a serious liberal and revolutionary spirit. Even with the artistic support of the king, it shocks me that they didn’t face more opposition from their government, or their religious leaders. They are presenting in their lyrics serious ideas about freedom and justice, and about destroying traditional power dynamics like slavery, or poverty. There are no silly love songs or obscure platitudes here. The songs are all intense, full of evocative imagery and fairly sophisticated ideas about ways they could transform their society for the better.

The film itself also follows a startlingly revolutionary bent. Some of the earliest shots in the film show the slums of Hay Mohammadi, in Casablanca, where the band mostly grew up. The images, which were nearly censored, are evocative of the clear poverty and shanty nature of these segments of Moroccan society. This is not a side of the country that you would expect to see presented. It’s even more incredible and rewarding to see them in a film that’s ostensibly a concert piece.

The film also shows footage of the funeral of Mohammed V, the beloved king of Morocco who was deposed by the French and then restored after independence. Given that his son and successor was suspected of having a hand in his untimely death, and given his immense popularity with the populace, it’s a revolutionary statement just to have this footage in the film at all. Again it’s amazing that the filmmakers got away with something so brazen. Watching this film, it was hard not to see the seeds of Arab Spring being sown in almost every scene.