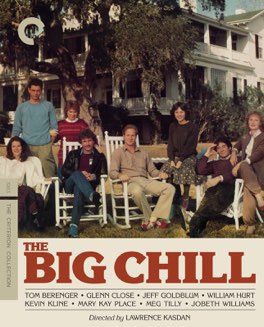

LAWRENCE KASDAN

The Big Chill

This film hit me like a ton of bricks. Apparently, from what I’ve read, it doesn’t have that effect on everyone. Many people seem to view it as trite, as an overindulgence by its famous director, Lawrence Kasdan of Star Wars fame, and dimiss it entirely. Intellectually I can see what they mean, this probably isn’t one of the great works of cinema. But, for me, it resonated harder than many other films I’ve seen have. I think it has something to do with where you are in your life when you see it, I suppose that’s true of all media actually, and I came to it at pretty much the perfect time.

It also probably helps that I’m predisposed to enjoy this kind of film, a film that isn’t necessarily about anything in particular. I’ve talked many times here before about my love of films that simply exist to show what certain people, from a singular time and place, were like, rather than being about any particular plot or story direction. This is definitely another of those films. The story starts with a phone call, and the news that a man named Alex, who is never seen in the film, has killed himself. Next we see his funeral, arranged for him by a friend from college who he had been staying with. His seven closest friends from those days have all arrived, and it’s clearly been a while since they’ve all been in the same place. Even though they all claim they can only stay for the funeral itself, that they need to rush back to their busy lives, they end up spending the entire weekend together, reconnecting and experiencing each other. Along the way they have a bunch of conversations that you can only really have with people you’ve known intensely. They fight, laugh, make up, love, have sex, and, ultimately, grieve.

I didn’t make most of my closest friends in college. I have some dear, dear friends from that part of my life, to be sure, but my “family before a family” came a few years later. Specifically they came where I’m currently living, in San Francisco, during the middle and end of my twenties. Just like the people in this film, I met a group of people that felt, and still feel, like members of a family I chose for myself. We had many, many adventures, grew together, got into stupid drama, fought, made up, had sex, grieved, and all the rest. But, while I’m still here in San Francisco, most of them have now left, searching for their own dreams, in cheaper parts of the country. I still love them, dearly, and they will always be family to me, but we are almost never all together anymore. There is a sadness there, a grief I feel while missing incredible times that are now gone. It’s a difficult thing to be surrounded by your favorite people in the world, all the time, and then have it taken away. It’s a hard thing to deal with. We still talk, certainly more than the friends in this film, but it’s just not the same. We’re all young enough that death, while it has happened to our group, is still as unexpected as it is to the people in this film. Because this is 2014, and not 1983, we’re also just beginning to create families of our own, marriages and children and all that, so we still get together on happy occasions. But someday, hopefully not soon, we’ll all be together for exactly the same reason as in this film, and I have a feeling it will go pretty much the same way. That’s almost certainly why this film hit me as hard as it did.

It’s a nice film, full of good acting and a truly phenomenal soundtrack, but my relationship to the idea of this group dynamic is what I connected with. I think the film itself could have been a lot less great and I would still feel like I do right now. I read an essay by Lena Dunham, someone I’m not usually much of a fan of, and she summed up almost perfectly the other side of this film for me. In her essay she talks about how this film, assuming you’re someone in your twenties or thirties now, is a glimpse into the life your parents almost certainly had when they were the age you are now. That they too had a group of people in their lives, at some point, that mattered as much to them as my friends matter to me. It’s so obviously true, and yet we never really think about it. I’ve seen the difference in my parents faces when they are around these people, they way they light up and live in their shared past. These are people they haven’t been geographically close to, in many cases, for decades, but there is still a different tone to the conversations they have. These are people who knew them when they were young, when their lives were entirely promise, instead of actuality, and so that part hit me hard too. The whole thing was a mixture of happiness, sadness, longing, and understanding. I think I’ll make a point to talk to some of those people from my life, as soon as is reasonably possible.