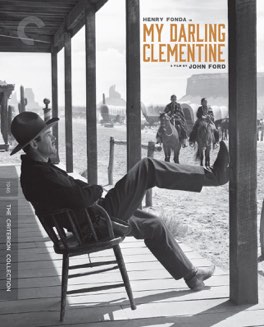

JOHN FORD

My Darling Clementine

Oh man I love westerns. There’s something that’s so unabashedly American about the genre.They represent a wholly American art form, solely concerned with American ideals. Only in a country built through the idea of manifest destiny could a genre like this exist, so full of pride and directness of purpose. The western, as a genre, is the perfect embodiment of the ideal of American rugged individualism, and the ridiculous hero worship we have for the cowboys that once roamed lonesomely across the wide open plains. I absolutely love it.

I also happen to absolutely love 1993’s Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer vehicle Tombstone, which is also an attempt to tell the story of legendary wild west lawman Wyatt Earp. I must have seen that film dozens of times, and I can quote whole sections of it without even thinking. So, watching this film it took me a second to divorce myself from the strangeness of seeing Henry Fonda and Victor Mature in the familiar roles of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holiday. However, after I got over my unease, I found a surprisingly deep film that I really enjoyed.

This film, much more than say Tombstone, focuses on the friendship between Wyatt Earp and Doc Holiday. As the film starts we find the four Earp brothers herding cattle near Tombstone, on their way to Mexico. After a chance encounter with Old Man Clanton, three of the brothers decide to venture into Tombstone for a shave and a drink. When they return, after Wyatt has kicked a drunk Indian out of town in an uncomfortably racist moment, they find that their youngest brother has been murdered and all their cattle have been stolen. Wyatt agrees to be the new marshal of the town and begins trying to clean it up, and to figure out what happened to his brother.

Attempting to bring some sense of law and order to Tombstone almost immediately brings him into contention with Doc Holiday. Holiday is running the primary saloon and gambling house and is somewhat concerned that having an actual marshal in town might not work out well for him. Quickly, however, he and Wyatt become friends, at least until his former girlfriend, the eponymous Clementine, shows up in town looking for him. The rest of the film concerns the complicated relationship between Holiday and Clementine, the relationship between Holiday and Earp, the attempts by Earp to bring his brothers killers to justice, and the eventual standoff at the O.K. Corral.

It’s a surprisingly mature take on the story of Wyatt Earp, especially for the era in which it was released. It’s a much darker film than many westerns of the period, with an almost film noir style of camera work. Interestingly it’s in black and white, even though color was by this point definitely an option. I think the use of black and white is a strong benefit to the story, it’s hard to imagine that it could look better with the addition of color, and we’d lose all the brilliant shadows that are so perfect here. This film could form a master class in how to frame a scene, it’s absolutely spectacular work by cinematographer Joseph MacDonald. The whole film is so somber in tone and feel, and seems to be reflecting on the nature of life, and of service to a cause, quite a bit more than I expected going in.

The film is also an absolutely fascinating example of what I was talking about in my opening paragraph. Much more than the previous John Ford film I reviewed, Stagecoach, this film represents the basic conceptions Americans have about the “wild west.” Here we have a group of brothers, traveling from the east to make some money in the wide open west, getting involved in small town affairs due to their code of honor. It’s really the classic American western story. The rugged man, who doesn’t really have a home anywhere, wanders into a situation he doesn’t really understand, and takes over. Wyatt Earp has no real idea about what’s going on with the Clanton’s, or Holiday, or Clementine, but he doesn’t need to. He just needs to do what’s right.

There is something so romanticized about the wild west in the consciousness of most Americans. At least there is in mine, and there has been my whole life. I’ve idolized the idea of the cowboy, out on the range, or getting in gunfights outside the saloon. Through a million westerns I’ve watched in my head, I’ve lived this story. I’ve been Wyatt Earp, and a host of other notorious western lawmen, and outlaws, and been involved in countless duels. I’ve won some, and lost some, but they are all sitting in my mind even now, just waiting to be replayed. I think every American boy, and probably plenty of girls too, have played this story out just as often as I have.

So, what is it about the American character that leads us to such a romanticization of the true story of the wild west. Certainly it wasn’t actually quite like this. The real wild west was a dangerous, racist, sexist, and shockingly dirty place. Full of crime, and small mindedness. I certainly don’t think I would like to actually live there, if I could suddenly be transported in time and space. And yet, in the fictionalized version that appears in films like this, the west represents the highest notions of our better nature. Ideals of honor and in doing what’s right, the idea of space to be yourself, and the chance to make your own way. These are all wonderful things, and this genre is the way we tell ourselves stories about them, and that’s why these films are so great. This one was certainly no exception; I really enjoyed it.