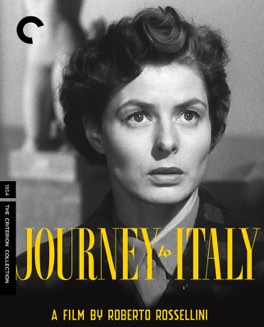

ROBERTO ROSSELLINI

Journey to Italy

This is a film about love, and the sort of breakdown in our normal lives that we sometimes need in order to take stock of what we have. It’s a lovely film, austere and yet beautiful. It’s full of incredible shots of mid-fifties Italy and wonderful performances by its main actors. It’s a very personal film, being somewhat autobiographical in its telling of the end of the love affair between star Ingrid Bergman and director Roberto Rossellini. It was made during a time when their love was beginning to fade, and I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to suggest that that might have motivated the story to a significant degree. It’s a fascinating examination of the kinds of walls we build around our lives, walls that can completely blind us to how we really feel about those supposedly closest to us.

The story revolves around Katherine Joyce and her husband Alex, who are newly arrived in Italy in order to settle the inheritance of an estate in Naples that belonged to Alex’s uncle Homer. From the very beginning we are shown that their eight year marriage is in serious trouble. The signs are extremely blatant and they seem to be everywhere. They aren’t communicating at all. She’s sensitive and sad, he’s aloof and bored. Their conversations are strained, and they only seem happy when they’re around other people. After a series of arguments and vicious jabs at each other, they separate, ostensibly to each enjoy their time in their own way. Really, though, they need some space to reflect and to decide how they feel about each other. Alex heads to the island of Capri, to flirt with woman and “have some fun.” Katherine, on the other hand, wanders around Naples, taking tours of museums and old relics. Slowly they both experience anger, jealously, sadness, longing, and distaste for each other. Eventually they come back to the estate, and, during a visit to Pompeii, begin to get down to the business of what they mean to each other and what they want for their future. What follows is one of the more interesting endings in modern cinema, one that I spent quite a bit of time reflecting on.

This film reminds me strongly of Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte, another film about the lies couples tell each other, and the truths they discover when they are finally forced to deal with each other. This film, however, despite being in English, is distinctly Italian. Where the Varda film is painfully, and delightfully, French in its stilted dialogue and romantic nature, this film is austere and straightforward, to an almost pathological degree. It’s a film that doesn’t couch its meaning in pretty words and speeches, but rather delivers it in striking blows. It’s an extremely interesting thing to see the same basic story told in such completely opposite styles. At least in terms of the story of the couple at its heart. The background, however, is handled much more similarly. Both films use their surroundings to provide narrative relief and interest. In La Pointe Courte the village and its inhabitants are the backdrop around the couple, here it’s the people of Italy and the relics of an ancient past. It seems like both characters are strongly influenced by the heat generated by the fabric of their Mediterranean surroundings. For him, it’s through the various people he meets, and for her it’s in the very stones that make up the relics she wanders through. The couple have built up a complete fiction about their marriage, that they have maintained by basically avoiding each other back home in London. Now that they are trapped in Italy, with no external obligations forcing them to do anything, they can’t run away from the fact that they are basically complete strangers.

The acting is really wonderful. Bergman isn’t my favorite star, but she’s perfectly cold and yet endearing as the wife in this story. Of the two she is presented much more humanely, possibly as a result of the autobiographical aspect of the film. George Sanders, who was maybe my favorite thing about Foreign Correspondent, is ridiculously British, a fact that works wonderfully for the point that Rossellini is trying to make about what happens when northerners journey to the hot temperament of the south. He doesn’t get an internal monologue, which Bergman does, and it makes him even more aloof and remote. His stoicism, even in the face of the complete dissolution of his life, counterbalances her obvious indecision and doubt. It also makes what happens at the end all the more surprising. Together they have a very interesting chemistry. Not conventional perhaps, but very authentic. It really seems like they are completely unsure of one another, that even after having spent eight years as a married couple they still have yet to really learn about each other. Their scenes together are at the very heart of the film, and given that Sanders was apparently cast just to give the film some box office heft, it’s a lucky chance that they play so wonderfully off one another.