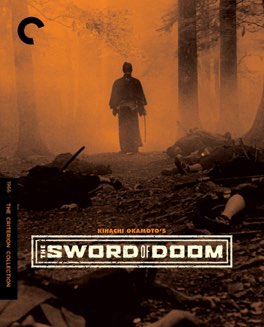

KIHACHI OKAMOTO

The Sword of Doom

This film is an example of chanbara, a sub-genre of jidaigeki, or period films, and Japanese for “sword fighting.” It’s a very common genre in Japanese film; the various Zatoichi films are also chanbara, for instance, as is Yojimbo. But this film is very different than they are. Both Yojimbo and the Zatoichi films are about the concept of Bushido, which means literally “the way of the warrior.” They focus on how a decent Samurai should behave, and are full of interesting ideas about duty and honor. That’s not what this is about. This film, on the other hand, is a reflection on the nature of evil, as well as a tribute to the beauty of violence.

The film follows the life of Ryunosuke Tsukue, a master swordsman who has been exiled from his fencing school for unknown reasons. From the first moment we see him in the film, we learn of his unrelenting cruelty to those around him. In the film’s opening scene, he murders a defenseless old man without even a pause. Soon after, he convinces the wife of a rival to sleep with him, before killing her husband in a supposedly non-violent test match. Eventually he ends up in a protracted standoff with the rival’s brother, as well as a master swordsman from a different school. Throughout the entirety of the film Ryunosuke is essentially without any trace of humanity or empathy.

The concept of the antihero is of course not a new one, going all the way back to Homer’s Thersites, but this is a different take than I’ve previously experienced. Typically, when an antihero is the protagonist of a piece of art, there’s some reason we the audience are made to root for him. That’s pointedly not the case here. Ryunosuke isn’t a particularly vile figure, but he’s most definitely not anyone you would want to side with. If anything I spent my time watching the film wondering exactly who of the more virtuous characters would get the honor of ending his villainy.

The film goes another way though, and that’s another aspect that made it unconventionally interesting to me. Ryunosuke never really gets any kind of traditional comeuppance. The closest we see to that is a very ambiguous ending, one that given the transcendent feats of swordplay we’ve seen him achieve in the rest of the film, doesn’t come close to shutting the door one way or the other. It’s a fascinating way to end the film, and what’s almost more interesting is that it happened mostly accidentally. This film is based on a well known epic novel, called the Daibosatsu Tōge, and this was only the first of what was initially anticipated to be a series of films. When this film didn’t perform at the box office the way Toho hoped it would, the rest of the series was canceled. Thus all we’re left with is this seemingly uncompleted story.

It sounds weird to say, but the lack of a traditionally closed ending didn’t bother me at all. Initially, not knowing the history behind it, I was a bit shocked at the abruptness. However, as I began to think about it more, it started to make more sense to me. This is a story about an almost primal level of evil, evil as a force, expressing itself through a vessel that happens to look like a human being. Ryunosuke isn’t intended to be an actual person, with personal issues that need resolving by the end of the film. In that sense, this can be viewed as more of a work of philosophy than any kind of traditional narrative. A meditation on the nature of evil as a force of destiny, rather than as a willful act. In that way, the ending makes perfect sense. Our antihero, doing what he does best, with no obvious motivation or intention, exactly the way nature always works.