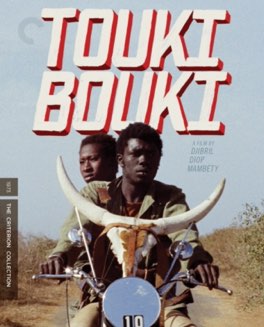

DJIBRIL DIOP MAMBÉTY

Touki bouki

I’ve been rather prolific lately, on something of a roll with watching these films, and writing here. That’s largely due to the election we’re all surviving right now. Film is my refuge, and it turns out even something as covertly political as this makes for a good, if fleeting, escape. This has been the scariest election of my lifetime, and the issues it has brought to the forefront will linger long after the results are finally, mercifully, known. This film, with its portrayal of two people who are treated like they don’t belong, resonates with everything that’s been going on.

The film tells the story of a young couple living in Dakar. They’re outsiders, constantly being told by their community they aren’t wanted. Unsurprisingly they also don’t want to stick around, and have grand dreams of moving to Paris. Unfortunately, their abject poverty makes leaving a virtual impossibility. Most of the film is spent following them try one get rich quick scheme after another, in search of a way to get enough cash to buy a boat ticket out. Finally they succeed in achieving what they believe is their dream, only to be confronted by the reality of what that choice actually means.

I’m a huge fan of the Scott Pilgrim series of comics. While that would seem to be about as far in texture and tone from this film as you can get, I see a connection. Specifically, one of the things that I love about Scott Pilgrim, is how it mixes everyday reality with the fantasy of video games. In this film, we see a fascinating amount of daily Senegalese life from this period. In addition, there are many elements that are purely fantastical, happening in the same space. This is a film made up largely of mystical dream logic, overlaid on ordinary reality. The heavily saturated color scheme helps to make the entire thing feel a little unreal.

The choice I alluded to, of whether to stay or go, is something I also relate with. It’s so often impossible to know how you will feel, or react, to a situation, until that situation is actually upon you. We may think we know. We may even do whatever we planned simply because we planned it. But there is no way to be completely certain of anything you feel until you’re feeling it. In some ways it makes life a bit scary. It’s also what makes it life. We cannot choose until we do, and, unlike history, we don’t know what’s going to happen until it does. It’s a powerful feeling to discover want you want, a point the film makes brilliantly.