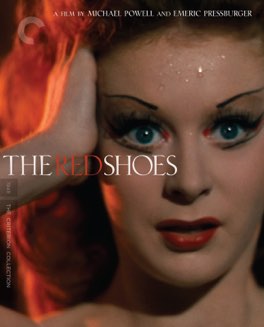

MICHAEL POWELL, EMERIC PRESSBURGER

The Red Shoes

Lately it seems like all I do is participate in blogathons, which is really not all that bad a place to be. As I’ve mentioned before, there’s something so great about the focus of choice that a blogathon provides. As someone who sometimes has real trouble with the paralysis of picking the next film to watch and write about for this site, it’s refreshing to narrow the possibilities significantly with a theme. This time I’m writing for the Gotta Dance! blogathon, hosted by Classic Reel Girl. The theme is to write about a film that prominently features dance, and this story of a ballet company seemed to be an obvious fit.

The film follows three primary characters. The first, Boris Lermontov, is the passionate and inflexible head of the ballet company which bears his name. The second, Julian Craster, is a young upcoming composer, who first attracts the attention of Lermontov when he accuses the impresario of using a score plagiarized from his work. Finally, Vicky Page, a young ballerina who secures an audition for the company by virtue of her declaration to Lermontov of her need to dance. The film follows as Lermontov turns both his new young pupils into stars, showcasing them in a truly incredible ballet sequence, and then as the whole thing falls apart when he discovers their love for each other.

The narrative is structured around a question I found interesting. That question is whether an artist can ever be truly great at their art, if they are not solely devoted to it. Lermontov spends most of the film proclaiming this point of view, including firing his original star ballerina when she announces to the company that she’s engaged to be married. He has a singular focus on the world of dance, to the point that he describes it as his religion, and he believes it requires complete dedication. The film itself mostly seems to support him in his view, portraying the cost of love as an abandonment of ones ability to be committed to their art. It’s repeatedly presented in order to fuel the tragic core of the story, and it works wonderfully as a narrative device.

On the other hand, the film also clearly seems to demonstrate it’s not an actual necessity. There is a period in the story, after Vicky and Julian have fallen for each other, but before Lermontov knows about it, that contradicts the central theme. Before he learns of their love, he detects no change in their abilities. To the contrary, both the composer and the ballerina are being raved about by everyone in the company, and the whole show has never been more successful. It’s only once Lermontov discovers their tryst that he decides their work is less than it has been, and it seems far more connected to his own dogma than to anything that’s really happened.

It could be argued then, that the tragedy is really about the inflexibility of the people in the story, not in the nature of art itself. Vicky is torn between her need to dance and her love for Julian, but only because Lermontov sets things up that way. Which is ultimately such a shame, because, in typical tragic fashion, it’s completely avoidable. Julian and Vicky are fueled by their love for each other, not hindered by it. Julian is writing great music so his love can dance to it, and Vicky is dancing her heart out for her man in the orchestra pit. They are finding the inspiration for their art in each other. If Lermontov was only able to realize it, the whole story could have gone very differently. On the other hand, the film wouldn’t have been nearly as good, so I don’t really want to complain that much.