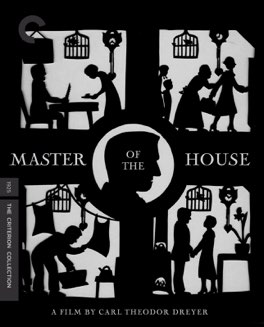

CARL TH. DREYER

Master of the House

This is a perfectly lovely domestic comedy, one that provides a view into the life of a 1920s lower-middle-class Danish family. Its director, Carl Theodore Dreyer, does a great job of creating a lived-in feeling for the world that his characters inhabit. I enjoyed the film, with its straightforward narrative of an out-of-work and tyrannical husband, being taught to appreciate all the hard work his wife does to keep their family afloat. I’ve spent much of my time since watching it though, pondering a narrative that I’ve seen widely reported; that this film should be considered a landmark early work of Feminism.

The film is a work of admirable restraint and it’s almost totally lacking in histrionics. Dreyer does a marvelous job of crafting the feel for the film, which takes place almost entirely within the cramped confines of the family’s apartment. He had working appliances installed, and filled up all the drawers, even those which were never intended to be opened. Dreyer believed that this attention to detail would make his actors feel more comfortable on set, and thus get better performances out of them. While I don’t have any proof that this technique worked, this is certainly a refreshingly honest film. The acting in particular is remarkably naturalistic, and, importantly for a story of this type, the husband it much more sarcastically rude than he is barbaric.

As for the politics, we have a tendency to view the past as though it was completely divorced from our clearly much more “modern” ideas. Anything we find that counteracts this notion is treated as though it’s a making a statement, rather than simply reflecting what were common positive attitudes of the time. So, from our perspective, the husbands of 1925 were all monsters, and it’s only now that they’re enlightened. That this is patently false is clear on both fronts; the men of the 20s were not all cavemen, and not all modern men are anything like fully enlightened. If anything, I’d say this film might make more of a political statement now, in our current world of culture wars and regressive notions of things, than it did in its own time.

The idea that “women’s work” had value was not a novel one in 1925, and there are many contemporary films that feature the narrative of men taking their wives for granted. From what I’ve read, only the most absurd Neanderthals of this time would have been offended, or shocked, by this premise. That this film comes off as more progressive than some seems more tied to Dreyer’s staunch belief in realism as an art form. So many films from this period were slapstick farce, and thus less impressive as any kind of statement. This film lacks any of that stagey overacting and demonstrativeness, and therefore has a much more serious feel to it, even as it’s a fairly innocuous story at its core.

I’ve gone back and forth as to whether I feel this film is particularly progressive. I think it’s a mixed bag. For one thing it’s still extremely gendered; the wife and daughter are responsible for doing basically all of the chores, while the son plays outside and the husband is out of the house. For another, when the wife finally does take a break from her family, in order to teach her husband his lesson, she essentially falls apart. She’s unable to cope with not doing the domestic chores she’s used to. While the husband does eventually begin to help around the house, it’s treated more as a temporary situation to learn to respect his wife, rather than any kind of statement about changing things in the future.

Maybe it’s not all that groundbreaking in its presentation of these issues, and maybe it’s been over hailed as some sort of larger statement. That’s perfectly fine with me, as it’s still a refreshingly humane story. And I was as surprised as anyone to see this relatively positive treatment of women, and enjoyed the ensuing education about this era. But, mostly, after watching films like Safety Last!, where I had to ignore racist stereotypes to enjoy myself, it’s nice to watch a film from this era where we can even have this debate. Certainly this is a nice narrative about the importance of understanding and respecting the work that so many women do. And while that may not have been a terribly revolutionary message for its time, it was still extremely enjoyable to watch, and definitely worthwhile, even if it’s not “important.”